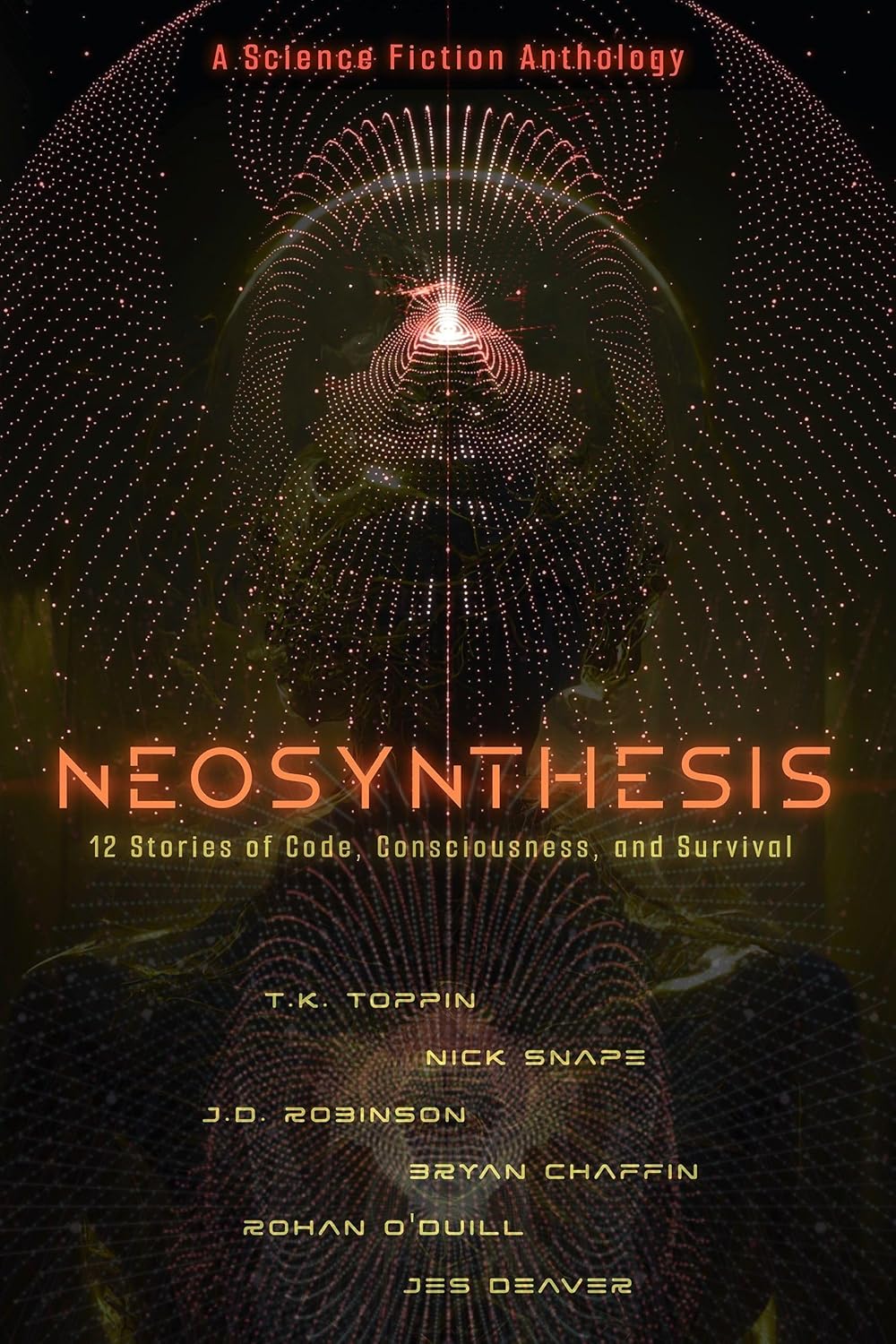

by Zilla Novikov

I finished this book at the end of 2025, and the question of the year is “What does it mean to be human versus machine?” This anthology tackles the question in the most human way imaginable–through science fiction. We see humans fight self-aware machines, or become them. We see the good and evil in the artificial, and in the humanity that programmed it. And we see robots replicate the best and worst of us.

This anthology isn’t a philosophy textbook. Most of the stories are packed with action, showing dynamic fights with lethal consequences. There’s love here too–doomed romance and deep friendship. My favourite was The Lore of Seven, where the stories we tell about where we come from are what make us who we are–even for a gang enforcer.