Every Tuesday, get to know a bit about the stories behind the books you love, and discover your next favourite novel.

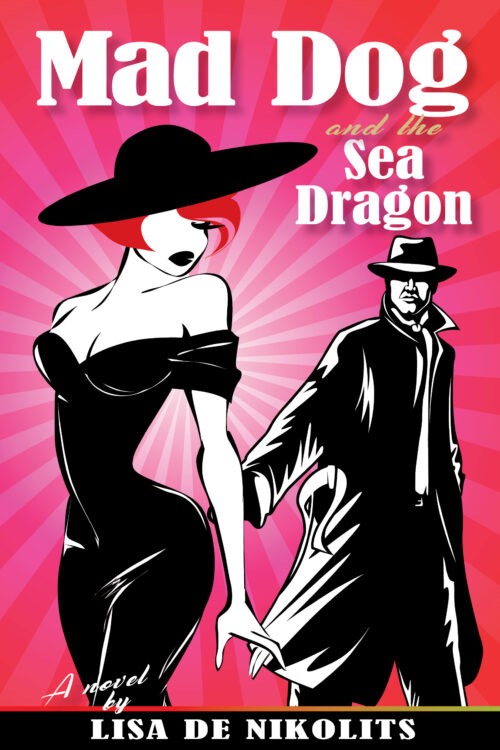

Zilla: From Blade Runner to The Expanse, Maltese Falcon to The Brick, noir has delighted audiences—not to mention readers. Lisa de Nikolits offers us her own take on the genre with a modern tale. Lisa, can you tell us about Mad Dog and the Sea Dragon?

Lisa: Mad Dog and the Sea Dragon is a modern-day noir caper with gangster villains of old and a glamorous kick-ass heroine. Murder, drug running, organized crime and danger, this book has it all, in a hard-boiled satirical style laced with dark humor.

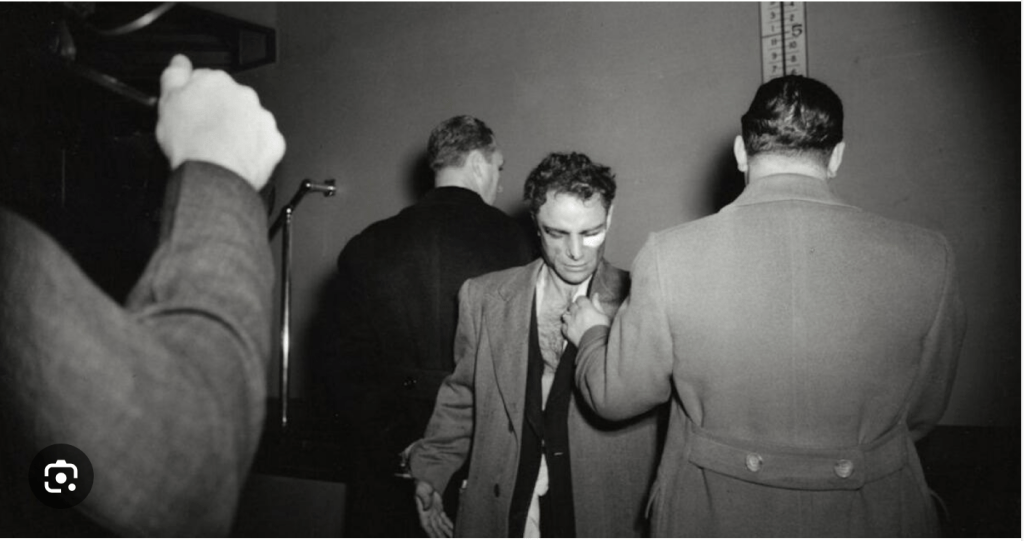

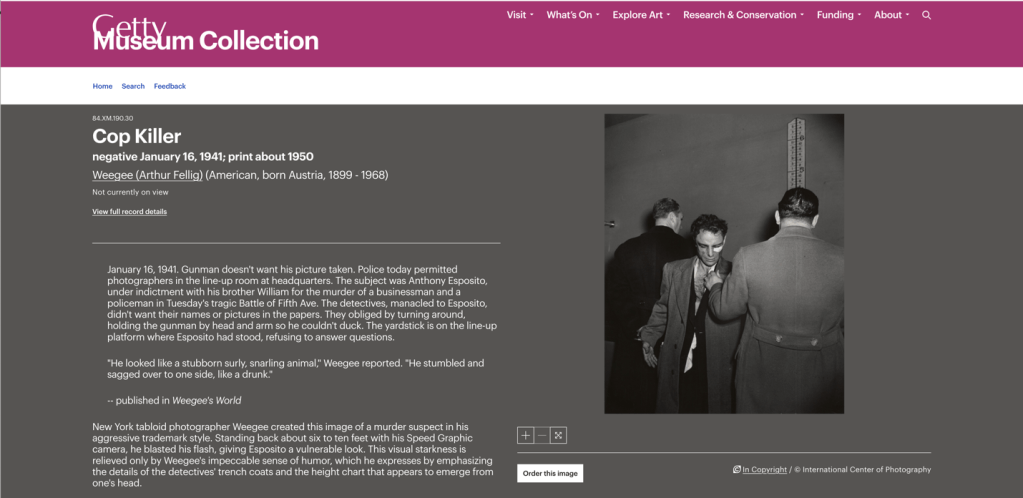

Zilla: Is there a visual image—a painting or a photo—that inspired you?

Lisa: An exhibit by Arthur Fellig featured a pic of Mad Dog Esposito. I immediately crushed on Mad Dog Esposito; his dishevelled sexiness, his moral anarchy, his casual, oversized trench coat, the torn shirt and ripped jacket revealing a manly chest with the right amount of chest hair, his handsome features completing his poster boy persona for a complete disregard for civilized life.

Zilla: If your characters met you, what would they say to you?

Lisa: Fascinating! In 15 years of interviews I’ve never been asked this!

JESSICA AND DONATELLA: CHAPTER 33

Donatella leads Jessica through a maze of dimly lit, thickly carpeted corridors. Jessica reflects that it wasn’t just the living room that looked like an African safari had taken root in the Swiss Alps, it was the whole house. The corridor smelled musty and odd, like cloves mixed with rotting carpets and mildew. Lisa rounds the corner and bumps into them.

DONATELLA

What you doing here, bitch? You gotta lotta nerve.

JESSICA

Yeah Lisa, what are you doing here?

LISA

Talk about a warm welcome. I wanted to know if you guys were happy with the way I wrote you.

DONATELLA

(laughs sarcastically)

You want our blessing? Bad timing, honey. But in general yeah, you did an okay job. But you coulda been kinda about the nose candy. I think you fell into a bucket of hyperbole.

JESSICA

Ignore her, Lisa. I’m happy too. I started out a bit spineless but I got my groove on. But couldn’t you have figured out something else for Daisy?

LISA

(chagrined)

I tried. I really did. I’m sorry.

DONATELLA

Yeah hug it out bitches, then Lisa, make like a magician and vanish.

Zilla:Is your work more plot-driven or character-driven? Or a secret, third thing?

Lisa: It’s a secret third thing! Imagine a kaleidoscope made up of a thousand different puzzle pieces, and those puzzle pieces are scenes from aquariums, movies, books, people I see on the subway, art galleries, overheard conversations, dreams (nightmares) of my own, late-night TV true crime documentaries at 2 am when I can’t sleep. And then I reach down into my heart and pull out a wish list of a book I’d love to have written. And then I set out to write it, and I spin the kaleidoscope until it makes sense – sense to me anyway, and then I pretend I’m on one of those reality TV shows where only one person makes it to the top of Mount Everest and I tell myself that I’m that person and then I write the book and nothing else exists until it’s finished.

Zilla: What’s your next writing project?

Lisa: In the Interests of Transparency, a novella, That Time I Killed You (coming in May 2026). “A story of iced cakes and malice, this compulsively readable novel about ordinary people doing very bad things will captivate you from the first page to the last.”

Zilla: Thanks for sharing your story and your process. We’re looking forward to reading! Where can the Night Beats community find you and your book?

Lisa: You can find me on Facebook and Instagram, or on my website. You can get my book on Amazon.