Every Tuesday, get to know a bit about the stories behind the books you love, and discover your next favourite novel.

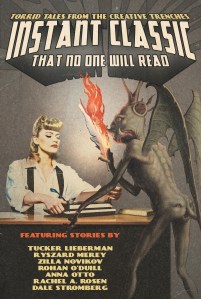

Sabitha: Here at Night Beats, we love a good meta story, and what’s more meta than stories about the making of stories? Two Night Beats authors, Tucker Lieberman and Rachel A. Rosen, join us to talk about Tucker’s stories in Instant Classic (That No One Will Read). Tucker, can you introduce us to the stories and the anthology?

Tucker: My story “Pygmalion v. Aphrodite” discusses an artificial intelligence that’s neither human nor divine. Humans create AI, and we like to believe we can profit from it, but it may transcend our control. Someday it might pursue its own artistic goals and earn its own money.

My other story, “Alicia’s Revision,” discusses how real-life experiences can be fictionalized. Multiple people can alter the fictional story. It may continue to change through layers of editing, pen names, and even theft. Wait long enough, and you’ll have a public domain story that belongs to everyone.

So many people are going to read Guaranteed Bestseller that, from the standpoint of its future fame, it won’t require me to explain it. But we aren’t in the bestselling future yet, so let me just say that it’s mostly about the frustration of not finding a publisher at all, never mind not having a plan to turn a published book into a bestseller.

Rachel: Both of your pieces deal with work in the public domain. How are these very old stories relevant to our contemporary lives?

Tucker: Pygmalion is an old myth that asks what art is trying to do: Imitate life? Be more perfect than life? Turn us on? It asks whether art is divinely inspired. It asks whether art could be brought to life or if perhaps it’s already alive. We’re asking similar questions today now that computers can form sentences and sketch images. Never mind whether art is divinely inspired; does it need to be humanly inspired? If it’s not, is it still art or is it just noise?

La Vorágine (The Vortex) is a famous Colombian novel that’s about to celebrate its centennial. The narrator is driven by lust and anger, and he waxes lyrical. In one sense, he de-romanticizes the jungle: it’s a place full of dangerous wildlife and exploitative bosses. But in another sense, Romantic sensibilities are central to the story, as the narrator is wrapped up in the exquisite self-importance of his own emotions. Long-form investigative journalists wrestle with how they show up in their stories, and so do a lot of novelists. When we warn of a social problem, how prominently should we feature in the message? Does it matter what we feel? How poetic should we be? Is our ego simply in the way?

Rachel: Your stories also deal critically with the question of authorship and who owns the stories that we tell. Can you tell me a little about your thoughts on the individual storyteller/intellectual property holder vs. collective storytelling?

Tucker: One person shouldn’t steal another’s creative work to profit from it. If the story fairy visits me in a dream and I spend a thousand hours writing a little book and pay a thousand dollars to an editor, I don’t want someone to lie that it was they to whom this happened and they who invested their time and money. They can’t slap their name on the cover and sell it. They can’t just take it without asking permission.

But in a more nuanced sense, art is co-created by a culture. Story ideas surface from other places, along with the language that forms them and clothes them. I’m just participating in the retelling. Besides, once a story’s in its new form, it’s up to readers to interpret it. Readers shouldn’t sell someone else’s story for dollars, but in more interesting ways, someone else’s story does belong to them. They’re allowed to make their own meaning with it.

Rachel: The story of Pygmalion is relatively well-known, whereas this is the first time I’ve come across La Vorágine. What drew you to each of these sources for inspiration?

Tucker: About 15 years ago, I thought of doing a Pygmalion retelling. I drafted a few paragraphs and forgot where I put them. Recently I uncovered those paragraphs, which had loomed ever-larger in my imagination, and was disappointed that they weren’t nearly as genius as I recalled. I started from scratch. The impetus was wondering what people think they are doing when they ask AI to bring stories to life. Is it different from, say, asking a goddess to bring something to life?

When I moved to Colombia, my Spanish teacher gave me La Vorágine as an abridged graphic novel. Now I can read the original. It’s a classic in Colombia. The writing prompt that drew me back to it was to imagine a classic novel with an unfortunate woman character and give her a better outcome.

Sabitha: Thank you both for this—I am so excited for this project! Where can readers get their hands on a copy? And where can they find your other work?

Tucker: The anthology is available for pre-order on Amazon, but if they want a free review copy, they can apply here—we just ask they post an honest review on a platform of their choice. I lurk on various networks at @tuckerlieberman, and tuckerlieberman.com directs you to my books, essays, and other crimes.